RESISTANCE METRO

SIGHT PLANS, SECTIONAL PLANS, DRAWINGS, ARCHITECTURAL MODELS

This project challenges the common portrayal of Gaza’s underground systems as mere “terror tunnels,” instead highlighting their socio-economic and cultural significance. These tunnels facilitate trade, education, and heritage preservation, embodying resilience amid decades of occupation and isolation. Focusing on Gaza’s Old City—particularly Souq Al-Dahab, the Great Omari Mosque, and the Mathaf Hotel—the research explores how these tunnels sustain cultural and community life. By examining decentralised and decolonised urban methodologies, the project underscores the role of subterranean systems in preserving Gaza’s social fabric and resisting the destruction of historical sites..

GEOLOGICAL TYPOLOGY

We analyze and research the depths and materiality of the tunnel, focusing on the soil types across Gaza and how the sandy terrain of Gaza facilitates tunnel construction, in contrast to the terrain in the West Bank. The types of sandy or loamy soils and terrain common in Gaza make it easier to excavate tunnels in contrast to other parts of Palestine.

Depths range from 15-60 metres- in contrast to the mountainous West Bank for example where you would need explosives to dig. However, plays as a disadvantage when it comes to destruction. The three main types of soil in the 365 sq. km. enclave are Sand Dunes, Loess, anc Calcareous sandstone

SITE PLAN AND TUNNEL ROUTES

Gaza’s tunnels are deeply linked to its history of resistance and survival. Eyal Weizman notes how each Israeli bombing campaign has driven Palestinian resistance further underground, leading to an increasingly sophisticated tunnel network. Initially built in 1982 to reconnect divided Rafah, these tunnels evolved into multifunctional pathways supporting trade, education, and movement of essential goods. Some tunnels extend 15 to 60 meters underground, demonstrating Gazan ingenuity despite relentless countermeasures.

While often labeled as “Hamas tunnels,” these networks have played a crucial role in sustaining Gaza’s autonomy. Testimonies we have collected reveal that they have been used to transport tools for restoring heritage sites such as the Byzantine Church and Souq Al-Dahab, fostering economic and cultural connections with Egypt. Rather than military infrastructure alone, these tunnels symbolise a spatial dialogue of survival and transformation, showing how they have enabled to keep Gaza’s population afloat.

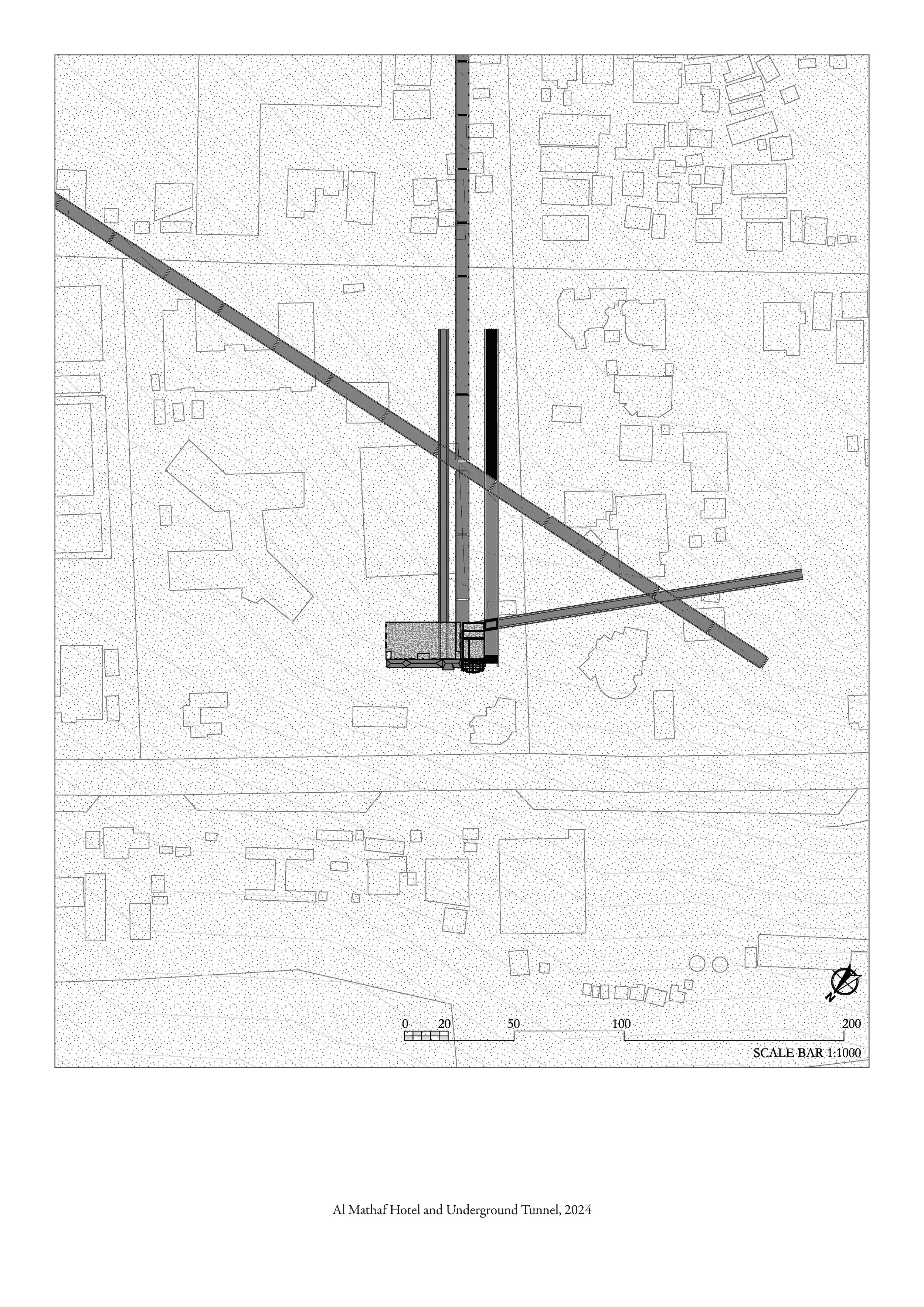

The Plan shows an aerial perspective how these structures connect different sites- further showing the structural complexities of the tunnels. This understanding is essential for appreciating how these networks serve multifaceted purposes—trade, education, cultural preservation, and even leisure activities.

ANALYSIS SITE ACCESS POINTS TUNNEL PORTAL LOCATIONS

Building on the idea of Gaza’s “Resistance Metro,” we explore how these tunnels—through their material presence—can serve as repositories of history, memory, and cultural expression. Beyond offering refuge, they can become spaces that protect life, honour heritage, and embody the stories of those within them.

We further challenge our proposal to question dominant view of tunnels as solely military infrastructure. Instead, we reframe them as sites of cultural production—reflecting Gaza’s enduring traditions of craftsmanship, art, and resilience. In a future liberated Palestine, these tunnels could stand not only as traces of survival under siege but as powerful symbols of healing, continuity, and cultural rebirth

DETAILED TUNNEL ROUTE

Reconstructed tunnel routes and depths according to testimonies of the existing archaeological Queen Helena tunnel discovered in 1927 through an earthquake: the thickest line (70 metres) is the deepest tunnel, drawing a straight route from the mosque to Shifa ( quick commutes in times of emergency), remaining the most indestructible. The main exit where all tunnels intersect again is Bab El Bahr. The second (60 metres) is as the Queen Helena Tunnel states, starting from the Omari Mosque to the Church of Saint Porphyrius to the Square and ending at Bab el Bahr. The third (35 metres) is the highest up and spans down south to the area where the universities are (exit point being at Aqsa mosque) - the longest route.

HISTORIC SITES ALONG ROUTE

The diagrams highlight the buildings and sites with the entries and exits, based on testimonies of Queen Helena, stating that the tunnel begins under the mosque, runs under the Ahli hospital, Palestine Square, and ends at Bab el Bahr. The other sites were selected due to their functional importance.

The Omari Mosque, the oldest and largest in Gaza, serves as a key tunnel entrance into the city’s historic core. Holding deep historical and religious significance, it was one of the first sites bombed and also marks the deepest tunnel in Gaza at 70 meters, with origins dating back 1,400 years .The Church of Saint Porphyrius, the third-oldest church in the world, also features a tunnel access point. It has historically been a central site for Gaza’s small Orthodox Christian community. Palestine Square, a vital green public space in Gaza, functions as a major social and political hub. Recently, it was the site of a hostage exchange and is now associated with the underground tunnel network, highlighting its strategic value. Al-Aqsa University anchors Gaza’s academic life and connects key city zones via tunnels, symbolising hope and continuity. Shifa Hospital, centrally located, bridges medical care and history through its link to the ancient Queen Helena tunnel. Bab el Bahr serves as the main tunnel exit, connecting Gaza’s east, west, and the sea—reviving its historic role in movement and exchange.

PLAN VIEW

AL MATHAF HOTEL GAZA CITY

A key part of our exploration is the materiality of the tunnels. Digging is more than survival—it’s a form of craft that shapes the earth much like casting shapes in molds. The soil, clay, and sand are not just materials but the foundation of this craft, embodying life, destruction, and time. Like pottery and casting, tunnels create and define negative spaces— vessels that hold memory, culture, and history. These hollowed-out forms become crafted objects where history is both preserved and actively shaped.

Our study examines this relationship on two scales: the micro, through traditional pottery and Qamariyah windows as moulded objects, and the macro, viewing the tunnel system as an underground mould, a vessel supporting communities and ecosystems. Each shovel of earth removed acts like a mold being formed—shaping space with intention and purpose.